Towards a new balance between human creation and AI

Artificial intelligence has become a central part of our daily lives. It generates texts, images, melodies, and even contributes to the development of technical innovations. However, this advance has sparked a legal and philosophical debate: can AI be the owner of intellectual property rights?

For now, the short answer is no. The world’s leading intellectual property offices require that the inventor or author be a human being. In the case known as “DABUS,” patent applications were filed naming as the inventor an AI (“Device for the Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Sentience”) developed by researcher Stephen Thaler. Between 2023 and 2025, courts in the United Kingdom, Germany, Korea, and Japan confirmed that only humans can be recognized as inventors, even if the system generated the invention autonomously. The case became a global benchmark and confirmed that, at least for now, artificial intelligence cannot hold industrial property rights, particularly invention patents.

Some authors argue that, in the near future, it may be necessary to redefine the notion of legal personality to include machines with autonomy and creative capacity. They even speak of a possible “robotic legal personality” that would allow certain rights or obligations to be recognized for intelligent systems. For now, that idea seems closer to science fiction than legal reality.

So, what can be protected by intellectual property rights in the context of artificial intelligence? It is important to distinguish between the different types of protection that exist. If AI generates an artistic or literary work, the result could be protected by copyright, depending on the territory, provided that there is a certain degree of human intervention in the creative process. In the case of an industrial design, its ornamental aspect may be protected, and in the case of a technical invention, a patent could be applied for. In all cases, the author of the work, the designer, or the inventor must be human beings, and the objects must meet the corresponding validity requirements (originality in the case of works; novelty and distinctive character for a design; novelty, inventive step, and industrial application for an invention).

In the case of patents, current practice recognizes “AI-assisted inventions,” i.e., developments in which artificial intelligence collaborates with humans and is used as a tool, but does not replace their role as inventors. Therefore, patents for AI-assisted inventions continue to be examined under the same criteria as computer-implemented inventions, for which there is extensive case law. Under this approach, it is also possible to protect generative AI technology involving a model or algorithm, provided that it meets the traditional requirements of novelty, inventive step, and industrial application.

In turn, since patents are not authorizations for use, there may be obstacles to exploitation when the development obtained with AI is based on training data or software protected by prior rights. A researcher may hold a patent on a new AI application, but if they used data or tools protected by third parties to develop it, they may need to obtain the appropriate authorizations in order to exploit it commercially.

This tension is evident in the debate over Studio Ghibli-style images. In 2024, various AI models began producing visual works that imitated the Japanese studio’s style, prompting complaints from creators’ associations and warnings about the unauthorized use of protected material in model training. In some jurisdictions, a “visual style” is not always protected by copyright per se, although the production of derivative or overly similar works could constitute infringement, e.g., if they reproduce well-known characters or scenes.

Some countries are already considering whether to establish specific exceptions for the use of data for training generative AI models. The idea would be to allow certain uses without infringing copyright, provided that conditions such as transparency, scientific purpose, or non-commercial use are met.

Artificial intelligence poses a challenge to the current legal framework. Its ability to create, learn, and evolve forces us to rethink the boundaries of authorship and intellectual property. We are in the process of redefining the relationship between humans and technology in a context where machines are no longer just tools, but creative actors with a real impact on the economy and culture. At the same time, the law will have the difficult task of finding a balance between protecting innovation, ethics, and common sense.

Innovation and development: how patents strengthen Argentina’s strategic industries

In the context of a macroeconomy seeking to regain predictability and a country with a solid base of strategic industries, new investment opportunities for entrepreneurs and companies are beginning to emerge. For technology-based businesses in particular, identifying, protecting, and leveraging their innovations can become a concrete competitive advantage in the market.

Registering a patent in Argentina allows companies to protect an intangible asset that can define their competitive position in the medium and long term. The patent system provides a legal tool that grants a temporary monopoly on exploitation and, at the same time, sends a message to the market that innovation has value and that there is interest in defending it. A patent is granted for 20 years from the date of filing the application and allows the owner to decide on the exploitation of their technology, negotiate licenses, or seek partners to commercialize it.

Strategic, thriving, and innovative sectors—where patent protection is essential—include agribusiness, pharmaceuticals, energy, and high technology. Argentina has a comparative advantage in biotechnology applied to agriculture, where genetic innovation, the development of bio-inputs, and precision solutions are at the heart of the business. In the pharmaceutical field, the country has national pharmaceutical companies with large installed capacity and a track record in R&D. In the energy sector, the shift toward clean technologies and more efficient processes is opening a race to register industrial innovations.

For its part, the knowledge sector is showing remarkable growth, and its share of the total economy is becoming increasingly significant. In 2024, exports of services related to this sector grew by 15.5% over the previous year, reaching US$8.927 billion. Today, the knowledge industry competes with the automotive industry for third place among the country’s export complexes, representing 9.2% of Argentine exports—only behind the agricultural and petrochemical sectors. The knowledge economy includes innovations related to information technology and software, artificial intelligence, and machine learning, among others.

In these industries that generate technology-based businesses, the same logic applies: to anticipate is to protect value. Patents not only offer concrete protection against unauthorized exploitation, but they also provide peace of mind to be able to make strategic decisions about the future of an invention.

Protecting innovation in our country should not be thought of solely as a defensive action, but as a central component of any business, investment, expansion, and development strategy. Argentina has the talent, infrastructure, and industrial capacity to be a major player in the coming decades. For that potential to translate into competitiveness, it is essential that entrepreneurs and companies have adequate protection for their innovations through patents within an ecosystem that favor obtaining and defending intellectual property rights.

Argentina and the PCT: an opportunity to boost innovation

Argentina is one of the few countries in the region that has not yet joined the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), an international system that enables the simplification, unification, and deferral of the costs of protecting inventions in more than 150 countries. This lack of adherence limits the tools available to local researchers, universities, and startups that develop technology with the potential to scale to other markets. Today, those who innovate from Argentina face more barriers than their peers in neighboring countries, not because of technical issues, but because of a pending political decision.

As Argentina is not part of this system, those who develop technology locally—universities, research centers, startups, SMEs—cannot file international PCT applications themselves, and in practice, this means higher costs, greater complexity, and fewer possibilities for protection for local developments with global potential.

Contrary to what many believe, the PCT does not change the underlying rules for granting patents in each country, nor does it limit the ability to examine and decide according to local laws. Its purpose is to simplify the process of international protection of inventions, facilitating a unified filing stage that defers costs, reduces bureaucracy, and allows for better strategic decisions along the way.

Joining the PCT is an opportunity to strengthen local actors. Public research institutions, many national universities, and technology entrepreneurs could benefit greatly from a more agile, centralized, and predictable pathway to obtaining rights abroad. Even well-established industrial sectors with export potential could find advantages in a system that organizes and facilitates processing in multiple jurisdictions.

The treaty allows for the deferral of the filing and processing of applications with national offices for up to 30 months, which not only alleviates the initial economic impact but also provides time to seek partners, validate markets, and decide in which territories to move forward. In addition, it allows for the centralization of certain procedures that would otherwise have to be repeated country by country—such as name changes, assignments, and priority documents—reducing associated costs, and also enables the access to an international search report and a patentability opinion prior to national filings. In this sense, the PCT also acts as a planning tool. It allows research and development teams to plan for the longer term, protect intermediate results, and assess in which markets it makes sense to invest patenting efforts. This flexibility is especially valuable for projects arising from academic or public institutions, where development times are often longer and resources more limited.

In terms of costs, the difference can also be significant. Initiating an international filing without the backing of the PCT requires simultaneous expenditures in multiple countries, in addition to managing different versions of the same application adapted to each jurisdiction. The current system imposes an administrative and economic burden on Argentine innovators that peers in other countries do not face. This structural disadvantage discourages early internationalization and often limits the scope of inventions with high potential.

In the current global context, where technological developments circulate at high speed and international collaborations are increasingly frequent, joining the PCT can represent a competitive advantage. It is not only a matter of facilitating filings, but also of expanding the options available to those who are creating value from Argentina.

In the regional scenario, the case of Uruguay is particularly interesting. The country joined the PCT in 2024. Although companies in the neighboring country are generally smaller than ours, they operate in an environment that provides more advantages to foreign investment. This combination of scale and openness has allowed Uruguay to take a step that better positions its ecosystem for opportunities for technology transfer and international collaboration.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that joining the PCT is not an isolated reform, but part of a set of possible measures to modernize the intellectual property ecosystem in the country. For years, various technical and academic voices have been proposing improvements in the digitization of procedures, greater predictability in deadlines, and support mechanisms for those who embark on the path to patenting. Joining the PCT system would be a step in that direction: a concrete improvement in line with the challenges currently faced by science, technology, and knowledge production in Argentina.

For the above-mentioned reasons, it is worth opening the debate from a constructive perspective. To consider how to add tools that strengthen the local ecosystem, with clear and predictable rules, aligned with international standards. Joining the PCT could be one of them: a decision that does not replace national mechanisms for granting patents, but rather complements them and multiplies opportunities for those who are already working on the present—and future—of Argentine innovation.

Claims and Description

Most patent laws establish that the right conferred by a patent is determined by its claims (see, for ex., Section 11 of the Argentine Patent Law, Articles 69 and 84 of the European Patent Convention (EPC), or paragraph 112(b) of Title 35 of the United States Code). Thus, the claims define the subject matter for which protection is sought (namely, the invention).

For this reason, the proper drafting of patent claims is of vital importance to an intellectual property strategy: the scope of the claim will be determined by the terminology used and will define which embodiments are covered.

For example, if a claim uses the term “vinyl polymer,” its scope will be broader than if it used the term “polystyrene” (a specific type of vinyl polymer). While this results in broader protection, it also increases the number of prior art documents that may affect patentability, as the scope of protection is inversely related to patentability.

Now, if the claims define the right and therefore constitute the “heart” of a patent, what is the role of the description? In short, the description must support the claims, and describe the invention defined by them in a sufficiently clear and complete manner.

On the other hand, patent laws establish that the description, which includes a written description and, optionally, drawings, is used to interpret the claims. In general, it is the patent offices or courts that decide how this interpretation is to be carried out. Moreover, these interpretations may differ from one another, as is the case in the United States (the “broadest reasonable interpretation” standard before the USPTO vs. the “ordinary and customary meaning as understood by a person of ordinary skill in the art in light of the description and prosecution history” standard applied by the courts).

It is also common for the same right holders to advocate for different interpretations of the same claims, depending on whether the goal is to assess the scope of the right in the context of infringement, or to analyze whether the invention meets the patentability requirements. In the former case, the right holder will tend to argue that the claim has a broad scope, allowing them to block a larger number of competitors, while in the latter, they will argue for a narrower interpretation to strengthen the patentability position.

In this context, a key question arises: what happens when the terms of a claim may be interpreted in a certain way “on their own,” but are defined or given a proposed interpretation within the description?

This question was recently addressed by the Enlarged Board of Appeal of the European Patent Office (EPO) in its decision G 1/24. This decision originated from case T 0439/22, in which the term “gathered sheet” had to be interpreted in the claims of patent EP 2 307 6804.

The usual interpretation would be “a sheet folded along lines to occupy a three-dimensional space.” However, the application indicated that the term should be interpreted as “corrugated, folded, or compressed or otherwise constrained substantially transversely to the cylindrical axis of the rod.” Using this latter interpretation, patentability—particularly novelty—was affected by prior art. For this reason, the applicant sought to distance itself from the interpretation proposed in the description, arguing that claim terms should be interpreted according to their usual meaning and that the description should be consulted only in case of doubt.

Three questions were posed to the Enlarged Board in case T 0439/22, including:

Can the description and drawings be consulted when interpreting the claims to assess patentability and, if so, can this be done as a general rule or only if the person skilled in the art finds the claim unclear or ambiguous when read in isolation?

In response, the Enlarged Board considered that there is no single legal basis for claim interpretation in the context of assessing patentability, as Article 69 of the EPC relates to the scope of protection for infringement purposes, while Article 84 sets formal requirements for the content of a patent application and does not refer to claim interpretation.

Nevertheless, based on the case law of the Technical Boards of Appeal, the Enlarged Board concluded:

“The claims are the starting point and the basis for assessing the patentability of an invention. The description and drawings shall always be consulted to interpret the claims when assessing the patentability of an invention, and not only if the person skilled in the art finds a claim to be unclear or ambiguous when read in isolation.”

This decision reaffirms the importance of the description in interpreting the claims in all circumstances. It also sets out guidelines for the alignment between the description and the claims —something that some EPO examiners were already strictly enforcing when requesting amendments to the description in line with the allowable claims following examination.

Decision G 1/24 may influence how courts, both in Europe and other jurisdictions, interpret the scope of protection of a granted patent, and reinforces the importance of precise drafting to protect the interests of right holders.

ChatGPT, Gemini, and Claude: The Intellectual Property Challenges Posed by Artificial Intelligence

When we think of generative artificial intelligence, platforms like ChatGPT, Gemini, or Claude often come to mind—with their impressive ability to draft text, generate responses in record time, create images, or translate with near-human fluency, among many other functions. But what we see is just the tip of the iceberg. Behind every interaction lies a complex infrastructure of massive datasets, advanced algorithms, and millions of trained parameters with significant economic and strategic value for these platforms. In the world of artificial intelligence, the processes, datasets, and architectures that make it possible are key resources to be protected as intangible assets.

In the early years of the modern AI boom, a culture of openness prevailed. Researchers shared findings, datasets, and open-source models. However, this mindset shifted with the rise of commercial interest and the growing need for legal protection of high-impact developments. Today, leading companies in the field are choosing not to disclose technical details of their most sophisticated models, marking a move toward confidentiality as a strategy to defend their value.

Ilya Sutskever, co-founder and Chief Scientist at OpenAI, admitted that openly sharing advances in artificial intelligence was a mistake. Although some of the datasets used to train models like GPT-4, Gemini, or Claude come from the open web, many include licensed content that remains undisclosed due to intellectual property and privacy concerns.

Adding to this is a growing challenge: the use of protected content without consent to train models. Millions of texts, images, and creative works have been used without authorization from their authors. In the U.S., artists have sued companies such as Stability AI and Midjourney. In 2023, The New York Times filed a lawsuit against OpenAI and Microsoft for the unauthorized use of its journalistic archive, arguing that these models are now capable of reproducing and directly competing with protected content—undermining entire business models.

In this new landscape, intellectual property is facing structural tensions. Patent applications related to AI have surged—with IBM, Microsoft, and Samsung leading the way—but many struggle to meet current eligibility criteria. In July 2024, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) updated its guidelines, clarifying that:

- Patent claims that describe specific hardware components or practical applications are more likely to be accepted.

- Purely abstract ideas—such as methods of organizing information or mental processes—are not patentable, as they are not considered inventions.

- Applications that involve model training with real-world technological impact (e.g., improvements in medical treatments) are viewed more favorably.

While generative AI is reshaping the global technological and economic landscape, the legal system is still adjusting its frameworks to keep pace with an unprecedented technological revolution.

In this context, having professional advice to manage intellectual property with a global and strategic vision is essential for navigating this environment and transforming knowledge into real, sustainable value. It requires an interdisciplinary and deeply contextual perspective—one that combines legal, technical, and strategic considerations. It’s not just about protecting assets, but understanding how they integrate into business models, how they are defended in potential disputes, and how they can be leveraged in highly competitive global markets.

Supporting innovation with solid intellectual property structures will be key to turning technological development into long-term sustainable advantages.

Taylor Swift, Her Masters, and Intellectual Property as a Strategic Asset

Recently, Taylor Swift made global headlines when she announced that, after years of litigation, she had repurchased the rights to the original recordings of her first six albums — known in the music industry as masters. The origins of the conflict date back to 2004, when Swift signed her first record deal with Big Machine Records at the age of 14. As is often the case in early contracts with emerging artists, she gave up ownership of those recordings in exchange for the support she needed to launch her career.

In 2018, when her contract ended, Swift attempted to regain control over those works. But Big Machine Records was acquired by entrepreneur Scooter Braun, who bought the entire catalog — including the masters — without giving Swift the opportunity to be involved in the deal. Then, in 2020, Braun sold the recordings to an investment fund, once again without offering the artist the chance to match the offer.

In response, the singer-songwriter decided to re-record her albums under the label “Taylor’s Version,” thereby weakening the commercial value of the original versions and generating the resources to buy back the rights to her masters. This was possible because her original contract included a clause allowing her to re-record her albums after a certain period following its expiration.

Beyond the media buzz, this case highlights how intellectual property assets — intangible yet strategic — are essential tools for protecting creativity, innovation, and their capitalization potential. Effective management of these assets requires an interdisciplinary approach that integrates technical, legal, commercial, and regulatory aspects. Simply registering an asset is not enough: it is crucial to accompany its life cycle, anticipate technological, regulatory, and business shifts, and design strategies to maximize its long-term value. In this regard, specialized and continuous advice is key for those aiming to transform creativity and innovation into a sustainable business while maintaining control over their future.

In the wake of Taylor Swift’s case, more artists may opt to license their masters rather than sell them outright. For their part, record labels are likely to become more reluctant to allow re-recordings of acquired masters, in order to prevent other artists from replicating the strategy employed by the American singer-songwriter.

Taylor Swift’s story shows that managing intangible assets is not a one-time action, but a long-term strategy. From registering her name as a trademark in 2008 to building a portfolio that includes song titles, iconic phrases, and elements from her narrative universe, she has successfully developed a personal brand with enormous commercial power.

In a context where innovation is accelerating and business models are becoming increasingly complex, intellectual property serves as a framework that structures, protects, and enables development. It is not merely a legal formality — it involves building assets that allow knowledge to be monetized, scaled sustainably, and strategically controlled as the business evolves.

In an increasingly globalized, digital, and dynamic world, holding intellectual property assets opens doors to new business opportunities. Proper management of these assets facilitates the creation of strategic alliances, access to international markets, and negotiation of licenses that boost revenue generation. Thus, IP becomes a competitive tool that can make the difference between the success or stagnation of an innovative project.

Whether we are talking about songs, software, chemical formulas, industrial developments, or trademarks, the message is the same: understanding, planning, and strategically protecting intellectual property assets is a necessary condition for leading the creative and commercial destiny of any project.

Elon Musk, Vaccines, and Coffee Capsules: Why Startups Must Protect Innovation?

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a global debate emerged about the need to waive vaccine patents. Some argued that, without intellectual property rights, it would have been easier to manufacture and distribute vaccines around the world. But the reality is more complex: without intellectual property protection, the innovations that made those vaccines possible likely wouldn’t have existed in the first place.

Although the COVID vaccines were commercialized by pharmaceutical companies, the mRNA technology on which they were based was developed at a U.S. university and protected through patents. That protection enabled the negotiation of licenses and attracted the investment needed to scale the technology in record time. Intellectual property was not an obstacle but an enabler of exploitation—it made the business viable and allowed the innovation to reach the market.

For startups, the lesson is clear: protecting technology through patents is neither excessive nor bureaucratic but an essential condition for attracting investors and capitalizing on a business. Patents give startups something they would not otherwise have: the exclusive right to exploit an innovation for a specific time and in a specific territory, which is crucial when resources are limited and competition can come from anywhere in the world. When obtaining a patent is not possible, there are other mechanisms of protection, such as designs, trademarks, and even copyright.

The exclusivity granted by intellectual property rights gives economic value to innovation in the eyes of investors who are looking for projects that cannot be easily copied or replicated.

The Coffee Capsule Case: Finding Where the Real Value Lies

A particularly illustrative example is that of a well-known coffee capsule brand. Instead of protecting only the coffee machine—a product relatively easy to copy—the company also protected the capsule’s design, its materials, and its piercing mechanism, which were the true heart of the business. While the machines could become a commodity, the capsules required specific licenses to be manufactured and sold. That smart intellectual property strategy allowed the company to control the consumer ecosystem and build a multi-million-dollar business.

The lesson for startups is that the greatest value often lies not in protecting everything, but in identifying the critical component that makes the difference—and then building the entry barrier for competitors from there.

The False Sense of Security Around Patentability

A very common misconception among entrepreneurs is failing to distinguish between patentability and freedom to operate. Having a patent means that an innovation meets the requirements to be patented, but it does not guarantee that it can be freely commercialized. There may be third-party patents in force that restrict or block the possibility of using the innovation. This issue was also particularly evident in the development of the COVID-19 vaccines: although the base technology was owned by a university, the pharmaceutical companies had to ensure they were not infringing on third-party rights in order to bring their products to market.

Many startups are unaware of this critical difference. Conducting a freedom-to-operate analysis—to verify that a technology does not infringe the rights of others—is a far more complex and sensitive process than evaluating patentability. That’s why it’s not always accessible in early stages, but it must become a priority when the product or service is ready to be launched on the market.

The Key Role of Investors and Incubators

Investors know this. They don’t just invest in ideas—they invest in intellectual property assets. It is increasingly common for incubators and accelerators not only to encourage the development of IP strategies, but even to finance them. In many cases, they directly require the existence of patent applications as a condition.

The message from investors to startups is clear: without intellectual property assets, there are no entry barriers; without entry barriers, there is no business.

That’s why protecting innovation is not optional: it is about building the asset on which all of a company’s value will be based.

There are well-known figures, like Elon Musk, who have recently made statements downplaying the importance of intellectual property. Musk has even said that “patents are for the weak.” But context matters: Elon Musk operates on a different scale—a global one—with a vast patent portfolio and a powerful brand reputation.

In conclusion, intellectual property does not hinder innovation—it drives it. It is what enables a startup to go from having a great idea to having a viable business that is attractive to investors and ready to grow.

Plausibility before the European Patent Office

On March 23, 2023, decision G 2/21 was published regarding the “Plausibility” of an invention before the European Patent Office (EPO). According to the understanding of the EPO’s Enlarged Board of Appeal, the plausibility of an invention is related to the possibility of supporting a technical effect upon which the inventive step relies, through experimental data or evidence submitted after the filing of the patent application.

The filing of data or experimental results after the filing of a patent application is a common practice in the patent prosecution process. In general, these pieces of evidence of the inventive step are generally accepted when they support or clarify a result obtained through the invention. The acceptance of these pieces of evidence varies depending on the territory or technical area, but they are generally accepted when the technical effect being demonstrated is disclosed in the application as originally filed.

The Technical Boards of Appeal of the EPO, in several decisions, considered cases in which the technical effect was not explicitly disclosed but could be deduced or considered by a person having ordinary skill in the art based on the information of the patent application, regardless of their common general knowledge. In other words, they considered situations in which it was either credible or plausible, or it was not non-credible or implausible, that a certain technical effect could be obtained through invention disclosed in the application as originally filed.

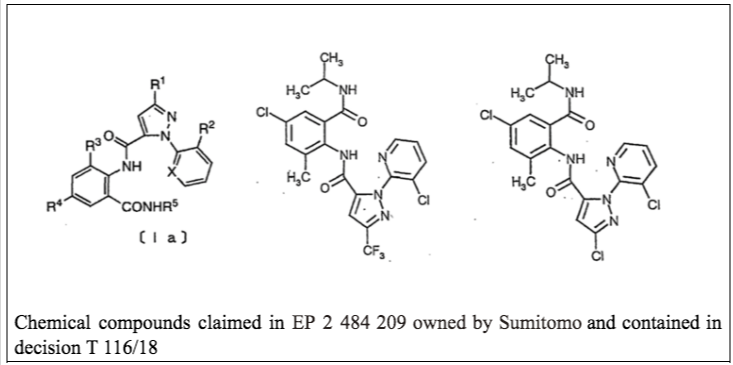

In this context, decision T 116/18 referred three questions to the Enlarged Board. In summary, the questions aim to decide on the admissibility of evidence subsequently submitted when the technical effect is not explicitly disclosed in the application as filed, but when this effect would be considered plausible by a person having ordinary skill in the art based on the information of the patent application (ab initio plausibility), or when there is no reason for the skilled person based on the information of the patent application to consider this effect as implausible (ab initio implausibility).

To answer these questions, the Enlarged Board affirmed in G 2/21:

- Evidence submitted by a patent applicant or proprietor to prove a technical effect relied upon for acknowledgement of inventive step of the claimed subject-matter may not be disregarded solely on the ground that such evidence, on which the effect rests, had not been public before the filing date of the patent in suit and was filed after that date.

- A patent applicant or proprietor may rely upon a technical effect for inventive step if the skilled person, having the common general knowledge in mind, and based on the application as originally filed, would derive said effect as being encompassed by the technical teaching and embodied by the same originally disclosed invention.

With this decision, the EPO reaffirms its position regarding the evidence submitted after the date of filing of a patent application, and which intends to support a purported technical effect.

It is important to highlight that the Enlarged Board reminds that this approach is applicable for inventive step, but that according to the current practice of the EPO, it would not be applicable for the assessment of sufficiency of disclosure.

Furthermore, according to the Enlarged Board, plausibility is not a new requirement for patentability, as it is novelty, inventive step, industrial application, and sufficiency of disclosure, instead, it “rather describes a generic catchword seized in the jurisprudence” as a criterion to support a purported technical effect. The concept of plausibility would be already included and considered in all other requirements, for which is not necessary to amend the laws related to patentability.

There are some territories with very restrictive practices for accepting evidence submitted after the filing date of a patent application. For example, in Argentina, for the prosecution of patent applications in the pharmaceutical field, these subsequent submissions are generally not accepted. The effect that this new decision by the EPO will have on the practice of other territories remains to be assessed.

Personalized medicine and patents

Personalized medicine is based on the administration of active ingredients to individuals sharing a specific biological feature. It relates to targeted therapies that search for the most appropriate treatment for a given patient, and that are usually presented as the promising future of medicine.

In many cases, the active ingredients used in these treatments are known compounds. However, determining the effective doses and the population for which such administration is therapeutically effective may involve experimental developments, as well as considerable economic efforts. In this context, it is of interest to know whether this “personalized medical use” resulting from research can be protected by a patent.

In other words, is it possible to claim a compound X for the treatment of disease Y administered to patients that share feature Z or, alternatively, a treatment for disease Y comprising administering a compound X to patients that share feature Z?

Under the European patent system, the possibility of second medical uses claims is provided by Art 54(5) EPC. A medical use of a known compound X may confer novelty to a claim directed to compound X for the treatment of disease Y, as long as said treatment does not form part of the state of the art. If a related technical effect is demonstrated, the therapeutic indication may be considered as a functional feature of the claim, conferring novelty to the claim in accordance with decision G 2/88 of the Enlarged Board of Appeal.

Later on, in decision G 2/08 of 2010, the Enlarged Board stated that a new mode of administration or dosage regime of compound X, or even the treatment of the same disease Y in a new group of patients, could contribute to the novelty of a medical use even if the general use of compound X for the treatment of disease Y were already known. This decision also set forth the prohibition of “Swiss type” claims for second medical uses under the European system.

In 2019, decision T 694/16 of a Technical Board of Appeal reaffirmed these principles and extended them specifically to personalized medicine. The case at issue was related to a known compound for the treatment of dementia, where the use of such compound in patients presenting a specific biological marker detectable in cerebrospinal fluid was claimed. According to patent EP2170104, this marker allows to distinguish between patients in prodromal phase, who will develop dementia, and patients presenting cognitive symptoms but who will not necessarily develop dementia. For the Board of Appeal, the selection of a subgroup of patients based on a feature Z (the common biological marker) may contribute to the novelty of a personalized medicine claim: the functional relationship between markers that characterize patients and the therapeutic effect which is sought is an essential technical feature of the claim. Moreover, prior art describing the use of compound X for the treatment of a disease Y in a group of patients including the subgroup having feature Z does not inherently or inevitably disclose this functional relationship and does not affect novelty of the claim.

With this decision, the European Patent Office confirms that it is possible to obtain European patents related to personalized medicine, even if the general use of an active principle in a determined treatment is known in the state of the art. To obtain a valid patent, the personalized treatment must also meet the inventive step requirement, meaning that it must not be obviously derivable from the prior art.

In Argentina, according to a Joint Ministry Resolution issued by the Patent Office and the Ministry of Health in 2012, second medical uses are not deemed patentable: nowadays, personalized medicine may hardly be the object of a patent of invention, regardless of whether novelty and inventive step criteria are met. Other Latin American countries accept second medical uses, as long as they are claimed according to local practice and all other patentability requirements are met.

In general, claims directed to uses are not accepted in the United States, although therapeutic methods for treatment are permitted. Nonetheless, the doctrine of inherency and anticipation practice under the US patent system may make it difficult to protect personalized medicine as compared to the European system.

EPO’s (final?) decision on patentability of plants and animals

The Enlarged Board of Appeal of the European Patent Office (EPO) confirmed in its most recent decision that plants and animals exclusively obtained by essentially biological processes are excluded from patentability.

This would be the final chapter in a debate that had the Technical Boards of Appeal of the EPO against the European Commission and the Administrative Council of the European Patent Organisation, and which may be summarised as follows:

- Article 53(b) EPC excludes from patentability essentially biological processes for the production of plants or animals.

- In 2015, the Enlarged Board of Appeal had concluded that this exclusion did not extend to plants or animals exclusively obtained by means of an essentially biological process, according to decisions G 2/12 (“Tomato II”) and G 2/13 (“Broccoli II”).

- In 2017, the European Commission promoted the amendment of Rule 28 EPC by the Administrative Council, based on the interpretation of Directive 98/44/CE, thus explicitly excluding plants and animals obtained exclusively by means of essentially biological processes.

- Recently, a Technical Board of Appeal refrained from applying amended R28, arguing that it would be contrary to the European Patent Convention, referring to the Enlarged Board’s decision of 2015.

- In the face of this legal uncertainty, the President of the EPO referred the question to the Enlarged Board in 2019.

- In Decision G 3/19 “Pepper”, the Enlarged Board changed its position and ruled that the exclusion from Art 53(b) also applies to plants and animals exclusively obtained by means of an essentially biological process.

In reaching this conclusion, the Enlarged Board adopted a dynamic interpretation of the Convention, recognising that the 2017 Rule amendment leads to an interpretation that is contrary to the 2015 decisions.

Furthermore, the Enlarged Board claims that this decision shall not have retroactive effect on European patents granted, or pending applications filed, before 1 July 2017, date on which the amended Rule came into force.

The foregoing would not modify patentability before the EPO of plants and animals that are not exclusively obtained from essentially biological processes. For instance, it would be possible to obtain a European patent for genetically modified plants or animals, as long as they are not obtained from traditional reproduction and selection methods.